The History of CNC System

The evolution of CNC systems began in the 1940s with the intersection of mechanical engineering and emerging digital logic. The first numerical control (NC) machines were developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), initially using punched paper tape to guide basic machining movements.

By the 1950s, NC machines were adopted in aerospace manufacturing to automate the production of complex parts. These early systems relied on analog electronics and followed relatively simple motion instructions with limited flexibility.

The shift toward computer numerical control (CNC) began in the 1970s, when microprocessors replaced analog circuits. This change allowed for more advanced features such as real-time program execution, storage of multiple machining routines, and the ability to control multiple axes simultaneously. It marked the foundation of modern digital manufacturing.

In the 1980s and 1990s, CNC technology became mainstream. Machine tool builders began to embed digital controllers directly into their equipment, and standardized programming languages such as G-code and M-code became widely used. This significantly improved compatibility between machines and enhanced operational consistency across production floors.

At the same time, different countries developed their own approaches to CNC innovation. Germany emphasized high-precision systems for automotive and aerospace sectors. Japan focused on compact and reliable controllers suitable for automated mass production. The United States prioritized flexibility and integration for industrial and defense applications. In China, national policies starting in the early 2000s promoted local development of CNC technologies to reduce dependence on foreign systems.

Components of a CNC System: Inside the Digital Brain

A CNC system is more than just a controller—it is an integrated architecture composed of multiple interdependent components that work together to execute precise machining operations. Each part plays a specific role, and the performance of the entire system depends on how well these components interact in real time.

CNC Controller

At the core is the CNC controller, the computing unit that interprets numerical code and sends coordinated instructions to other subsystems. It receives machining programs (usually in G-code), calculates tool paths, compensates for tool geometry and positioning offsets, and manages the timing of all machine actions. Modern controllers are based on microprocessors or industrial PCs, and typically include both real-time control and a human-machine interface (HMI).

Human-Machine Interface (HMI)

The HMI (Human-Machine Interface) is the user-facing panel where operators load programs, adjust settings, and monitor execution status. It often includes a touchscreen or button-based interface with visualizations of tool paths, machine diagnostics, alarms, and real-time data.

Servo Drive System

To convert digital instructions into physical motion, the system relies on the servo drive system. This includes servo motors, motor drivers, and position feedback devices. Servo motors precisely control each axis (such as X, Y, Z, or rotational axes), while encoders or linear scales provide real-time position feedback to ensure the commanded motion is accurately followed—a process called closed-loop control.

I/O Module

Another crucial component is the I/O module (Input/Output interface), which connects the controller to various machine actuators and sensors. It controls auxiliary functions such as spindle on/off, tool clamping, workpiece loading, coolant flow, lubrication, and safety interlocks. The I/O system acts as the nervous system of the machine, relaying signals between mechanical parts and digital logic.

Spindle Drive Unit

The spindle drive unit is dedicated to controlling the rotation of the spindle, which holds and spins the cutting tool. It operates independently of the linear axes but must be synchronized during operations like threading, tapping, or contour milling. Spindle speed, torque, and direction are all managed through the CNC controller via the drive.

Memory and Data Communication

Modern CNC systems also include memory and data communication modules. These enable program storage, backup, file transfer (e.g., via USB, Ethernet, or industrial protocols like EtherCAT), and remote monitoring. In larger factories, they also integrate with DNC or MES systems for centralized control.

Optional Automation Components

Some CNC setups use automatic tool changers (ATCs), probe systems, or adaptive control modules. These are optional extensions that expand automation capabilities, allowing machines to switch tools automatically, detect part positions with sensors, or dynamically adjust cutting parameters based on sensor feedback.

In short, a CNC system is a tightly integrated framework of computing, control, motion, and sensor technologies. Each component—controller, HMI, servo drives, I/O, spindle, and memory—is essential to achieving the high speed, accuracy, and reliability expected in modern machining environments.

How CNC Systems Work: From Code to Motion

A CNC system operates by interpreting a program—typically written in G-code—that defines every machining step, including movement paths, spindle speeds, and auxiliary actions. Once the program is loaded, the controller reads each line of code and translates it into control commands for motion, rotation, tool changes, or I/O functions. These commands are then issued in real time to different subsystems of the machine.

To execute motion, the controller calculates precise axis trajectories and sends position targets to the servo drive system. The drives activate motors to move the machine’s axes while continuously receiving feedback from encoders or sensors. The CNC system compares the actual position with the programmed position and adjusts dynamically to ensure accurate path following—this is known as closed-loop control.

At the same time, the system manages spindle operation, coordinates feed rates, and triggers functions like coolant flow or tool changes through the I/O interface. It also performs automatic coordinate transformation and tool compensation to account for offsets and geometry differences. These internal calculations and real-time adjustments ensure that the machine follows the program precisely, with repeatable results and minimal operator intervention.

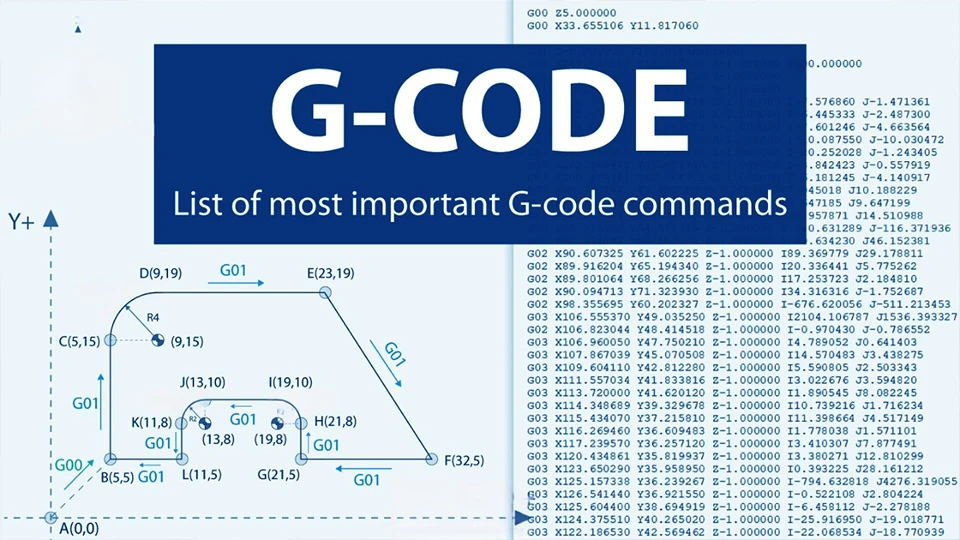

Common CNC Programming Languages

CNC systems rely on standardized programming languages to define machine actions in a format the controller can interpret. The most widely used language is G-code, a line-by-line numerical command format that controls motion and machining processes. It specifies instructions such as linear movement (G01), rapid positioning (G00), arc movements (G02/G03), and coordinate positioning.

In addition to G-codes, CNC programs include M-codes, which handle machine-level functions unrelated to axis motion. These include commands like spindle start (M03), spindle stop (M05), coolant control (M08/M09), and tool changes (M06). While G-codes manage “where” and “how” the machine moves, M-codes control “what else” happens during the process.

CNC programs also rely on auxiliary codes to specify machining parameters. For example, F codes define feed rate (e.g., F100.0), S codes control spindle speed (e.g., S1200), T codes select tool numbers (e.g., T02), and D codes may refer to tool diameter offsets. These values work in combination with motion and machine commands to ensure proper cutting conditions for each operation.

Each CNC controller brand may support slight variations or extensions of standard G-code formats. However, the core structure remains consistent: programs are written in blocks, each containing one or more codes with parameters, executed in sequence. These blocks enable the CNC system to carry out complex machining operations step-by-step with high precision.

Some advanced CNC systems also support macro programming, allowing conditional logic, loops, variables, and subprogram calls to reduce code redundancy and improve flexibility. This is especially useful in automated or batch production, where similar operations repeat across different parts.

Overall, understanding G-code and M-code is fundamental to CNC operation, serving as the basic language through which instructions are transmitted from program to machine.

Common CNC Programming Software and Tools

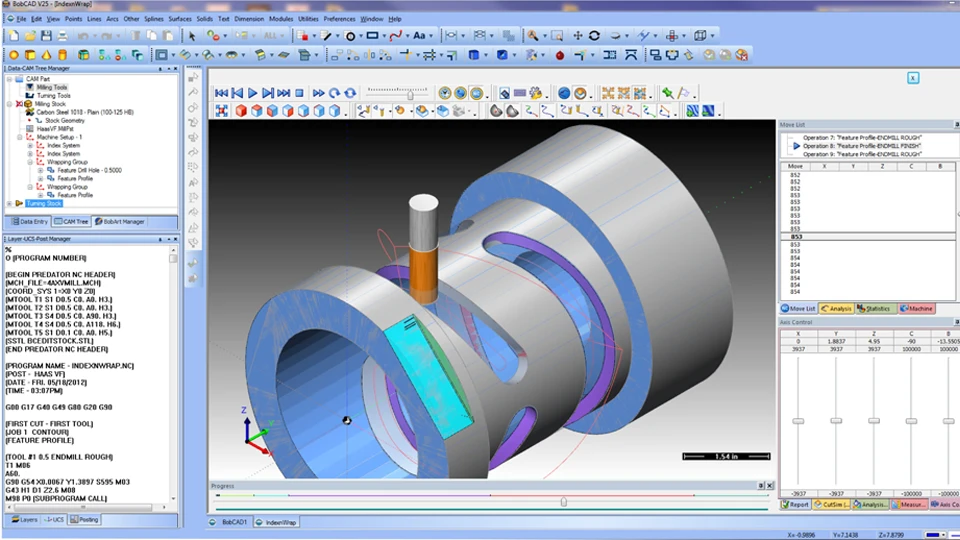

CNC programming relies on a range of specialized software tools to assist engineers and machinists in preparing, verifying, and optimizing machining programs. These tools typically work in stages—from part design to toolpath generation to simulation and final code output—each serving a unique role in the workflow.

At the design stage, CAD (Computer-Aided Design) software is used to create 2D drawings or 3D models of the workpiece. Popular CAD platforms include AutoCAD, SolidWorks, and Siemens NX. These models form the geometric foundation for subsequent programming steps.

CAM (Computer-Aided Manufacturing) software takes the CAD model and generates machining toolpaths based on user-defined parameters such as cutting strategy, tool type, material, and tolerance. Common CAM software includes Mastercam, Fusion 360, PowerMill, and Edgecam. CAM systems automatically output the corresponding G-code based on machine configuration and post-processor settings.

Simulation tools are often integrated within CAM environments or used as standalone platforms. They allow users to visualize tool movements, detect potential collisions, verify machining logic, and estimate cycle times before any physical cutting begins. This step helps prevent costly errors and machine downtime.

In addition to CAD/CAM systems, code editors and debugging tools are essential for fine-tuning or manually writing CNC programs. These editors typically include syntax highlighting, program structure analysis, and compatibility checks with specific controller formats. Some examples include NCPlot, CIMCO Edit, and Predator Editor.

Advanced programming environments may also include virtual machine simulation, adaptive optimization algorithms, and integration with tool libraries or material databases. While not mandatory for basic applications, such tools are increasingly common in high-mix, high-precision manufacturing environments.

By combining CAD, CAM, simulation, and editing tools, programmers can efficiently generate accurate CNC code, reduce trial-and-error, and streamline the transition from design to production.

Benefits of CNC System in Industrial Manufacturing

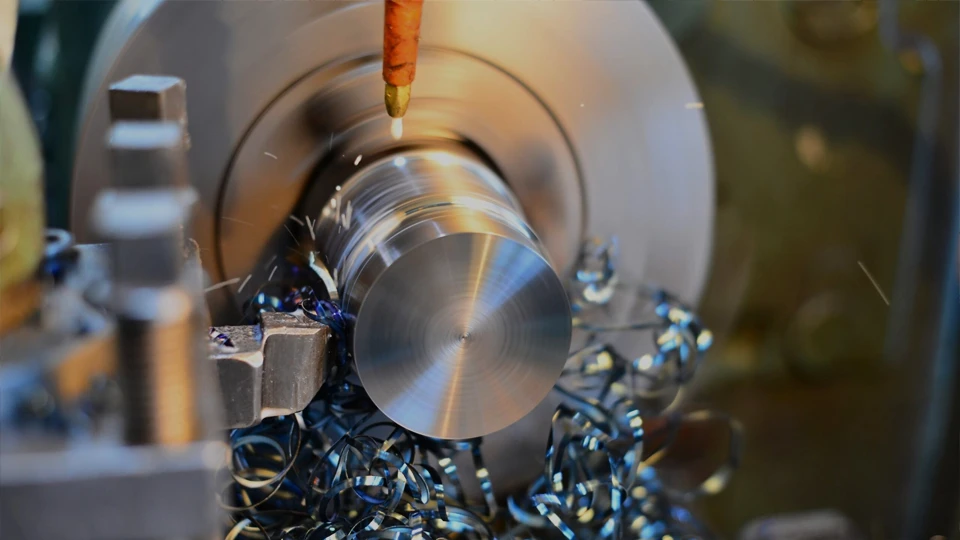

Higher Machining Accuracy

CNC systems achieve precision levels that far exceed manual machining. Through servo-driven closed-loop control and digital interpolation, they can maintain micron-level tolerances on complex geometries. This high accuracy is critical in industries such as aerospace, medical, and precision electronics, where dimensional integrity directly impacts product performance.

Consistent Results Across Mass Production

Once a CNC program is validated, it can be executed repeatedly without deviation. This ensures every part in a production batch meets the same specification, reducing variability and inspection effort. Such consistency is especially valuable in mass production environments where quality uniformity is non-negotiable.

Higher Automation, Lower Labor Dependency

CNC machines automate not only motion control but also spindle commands, coolant flow, and tool changes. This reduces reliance on operator skill and allows unattended or lights-out manufacturing. A single technician can manage multiple machines, optimizing workforce utilization.

Capability for Complex Part Geometries

With multi-axis control, CNC systems can produce intricate contours, angular features, and compound surfaces that manual machines cannot replicate. These operations are executed within a single setup, minimizing fixture changes and ensuring tight geometric correlation between features.

Predictable Cycle Times and Process Control

Feed rates, spindle speeds, and tool paths are precisely defined in the CNC program, allowing accurate estimation of machining time and material removal rate. This predictability improves scheduling, enhances efficiency, and supports lean manufacturing strategies.

Challenges of CNC System in Industrial Applications

While CNC systems provide numerous advantages, they also introduce specific challenges that manufacturers must account for when planning investment and operation. These issues often relate to system complexity, technical requirements, and long-term cost control.

High Initial Investment and Lifecycle Costs

CNC systems require significant upfront investment—not just for the hardware, but also for compatible controllers, servo systems, and industrial networking. Additionally, ongoing expenses such as software licensing, firmware updates, and controller-specific training can contribute to a high total cost of ownership, especially for small and medium-sized manufacturers.

Sensitivity to Harsh Environments

Unlike conventional manual controls, CNC systems depend heavily on electronic components, such as circuit boards, processors, and digital feedback systems. These components can be sensitive to extreme temperatures, humidity, vibration, and electrical noise. Without proper enclosure and environmental protection, the control system’s reliability may suffer, especially in heavy-duty or outdoor machining setups.

Maintenance and Troubleshooting Complexity

As CNC systems become more sophisticated, maintenance requires higher levels of technical expertise. Diagnosing issues within closed-loop control systems, multi-layer I/O networks, or integrated software platforms demands trained personnel and sometimes manufacturer-level support. Even minor controller errors or sensor failures can halt production until resolved.

Software and Compatibility Challenges

CNC systems rely on precise communication between CAD/CAM software, post-processors, and the machine’s firmware. Incompatible file formats, outdated post-processors, or inconsistent G-code interpretation across different controller brands can result in errors, tool crashes, or inefficient toolpaths. Managing these software variables requires standardized workflows and careful version control.

Conclusion: The Role of CNC Systems in Future Manufacturing

As manufacturing continues to evolve toward higher precision, greater flexibility, and digital integration, CNC systems remain the brain behind this transformation. From their origins in basic code-driven automation to today’s intelligent, feedback-driven platforms, CNC systems have redefined what’s possible in machining. Their ability to deliver consistent quality, enable complex part production, and integrate seamlessly with CAD/CAM workflows makes them not just a technology—but a foundation of modern industrial capability.

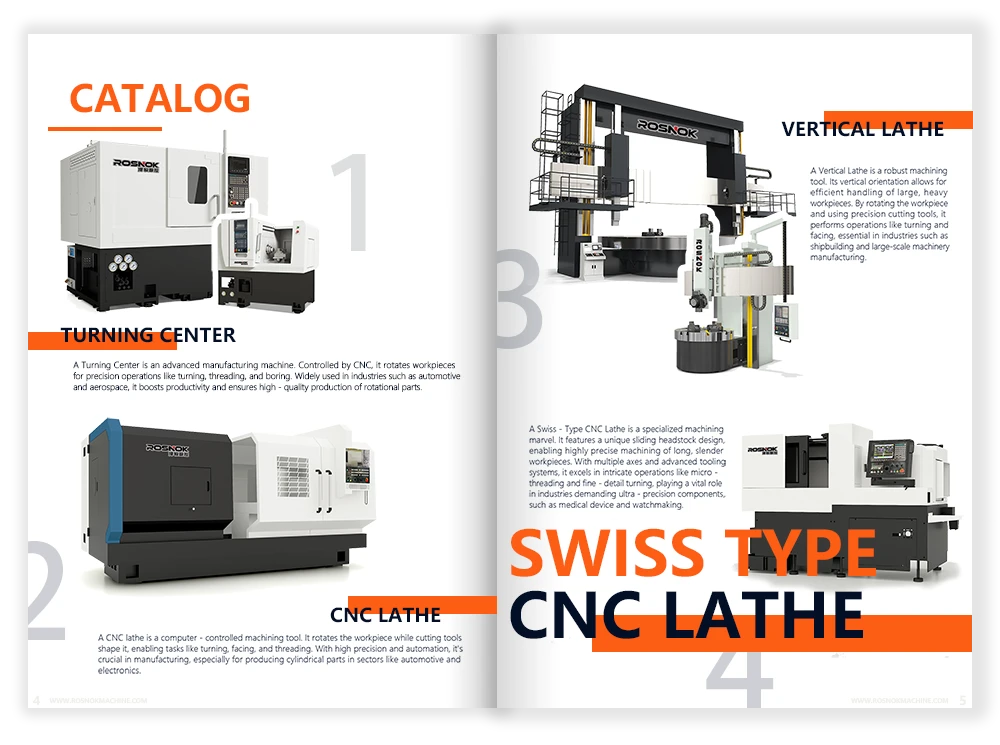

And while the landscape of CNC technology continues to advance, the machines powered by these systems must be just as reliable and forward-thinking. That’s why companies like Rosnok, with deep expertise in designing and manufacturing CNC machine tools, play such a critical role. By combining precision control systems with robust mechanical design, Rosnok ensures that industrial users get the full advantage of what CNC can offer—accuracy, repeatability, and long-term productivity.