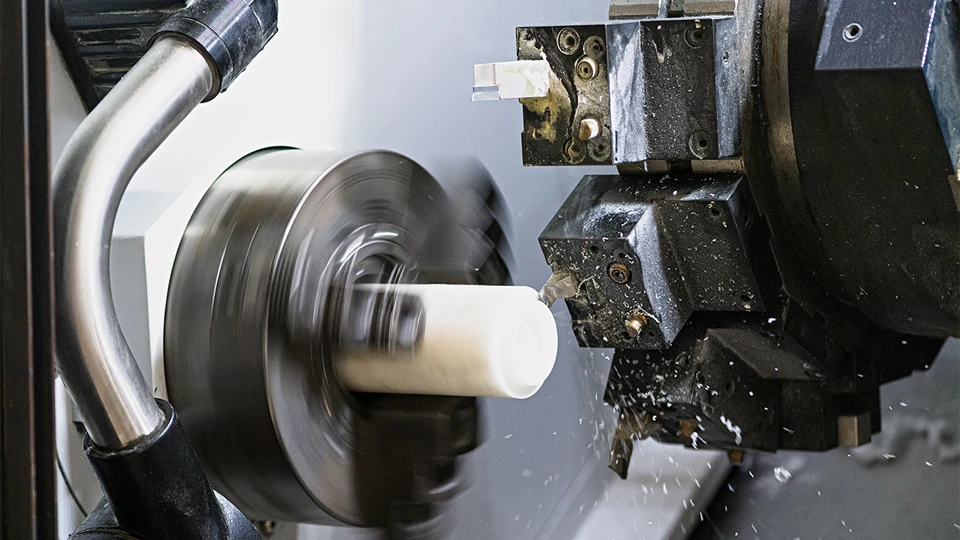

CNC Machining Materials define the outcome of every precision part we produce. From lightweight aluminum and resilient steels to advanced plastics and composites, each material behaves differently under the cutter. Some offer superb surface finishes but poor heat stability; others handle extreme stress but challenge tool life. Understanding these materials is the first step toward precision, consistency, and efficient production in any machining project.

In this comprehensive guide, I’ll walk you through a complete list of CNC Machining Materials used in modern manufacturing—covering metals, plastics, and specialty composites. You’ll learn their unique characteristics, machining behaviors, and typical industry applications. Then, we’ll move beyond the data: I’ll show you how to evaluate these materials scientifically, balancing machinability, strength, precision, and cost, so you can choose with confidence—not guesswork.

We’ll start with a clear materials overview, then build a decision framework that transforms data sheets into practical choices—helping you select CNC Machining Materials that align with your design, tolerance, and budget goals.

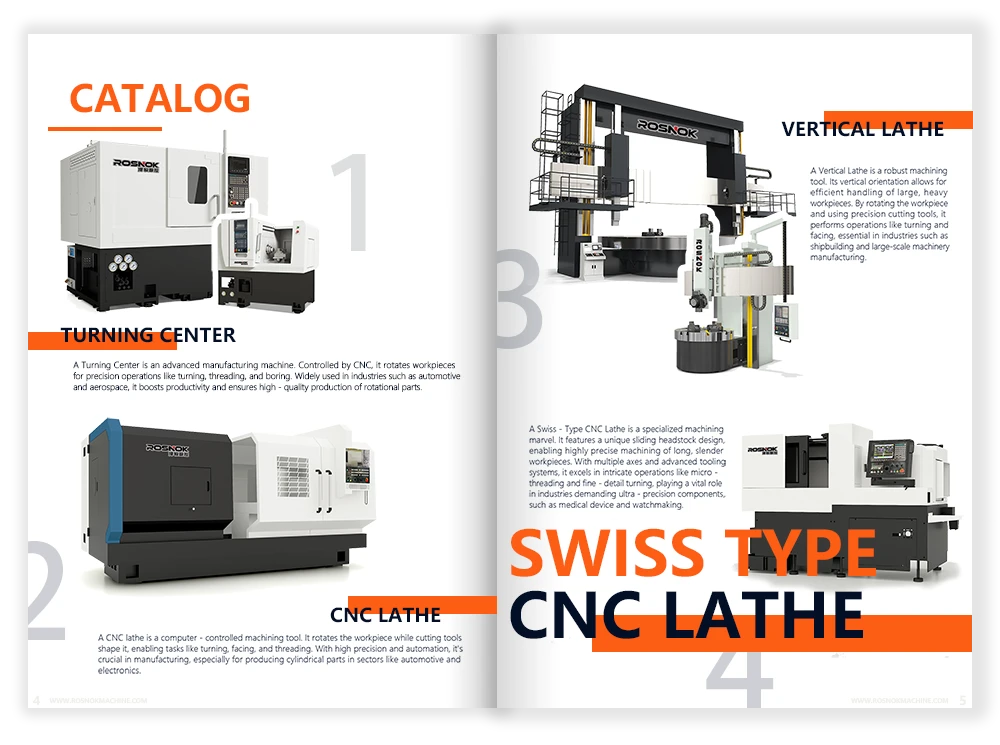

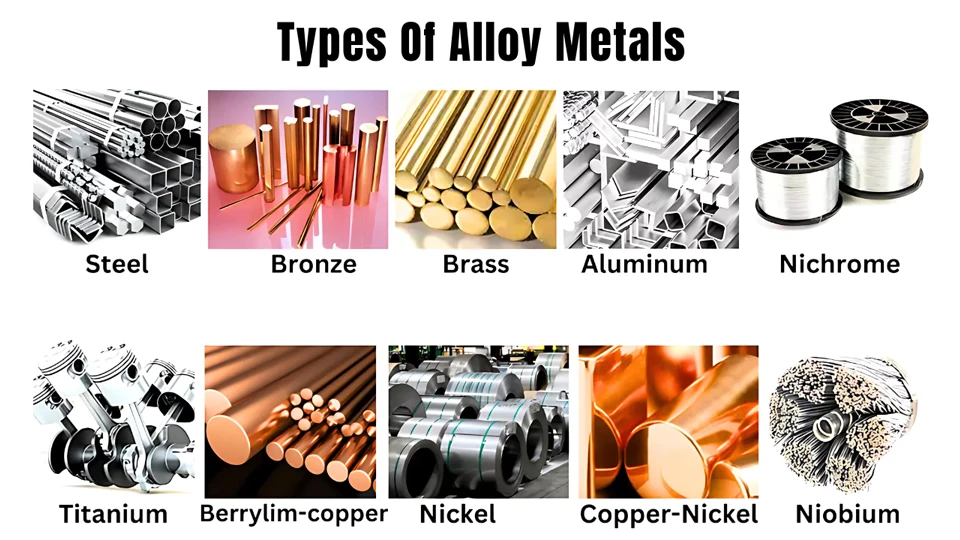

CNC Machining Materials Overview

Metal Materials for CNC Machining

Metal materials remain the backbone of CNC machining. They deliver strength, structural integrity, and precision for critical applications—from aerospace engine mounts to automotive shafts. In my experience, understanding how each metal reacts to cutting forces and heat is what separates efficient machining from expensive trial-and-error.

Aluminum Alloys

Aluminum is the most widely used CNC machining material because of its excellent machinability, light weight, and corrosion resistance.

- Common grades: 6061, 7075, 2024, 5083.

- Properties: High strength-to-weight ratio, good dimensional stability, and clean surface finishes with minimal tool wear.

- Applications: Aerospace structural parts, automotive housings, electronics enclosures, and prototypes.

Among them, Aluminum 6061 remains the industry standard for general machining—affordable, reliable, and easy to finish. 7075, with its higher tensile strength, is preferred in aerospace or performance applications where rigidity matters.

Steel and Stainless Steel

Steel combines strength, heat resistance, and versatility—but it’s harder to machine than aluminum.

- Common grades: Carbon Steel 1045, Alloy Steel 4140, Stainless 303, 304, 316L.

- Properties: Excellent mechanical strength, good wear resistance, variable corrosion resistance (depending on alloy).

- Applications: Shafts, gears, fixtures, and industrial machinery.

Stainless steel grades like 303 are optimized for machinability, while 316L offers exceptional corrosion resistance for marine or medical environments.

Brass and Copper

When machinability and conductivity matter, few materials outperform brass and copper.

- Common grades: Brass C360, Copper C110.

- Properties: Outstanding machinability, superior electrical and thermal conductivity, excellent corrosion resistance.

- Applications: Valves, connectors, electrical terminals, and fluid fittings.

Brass C360 in particular machines smoothly with minimal burr formation, making it a favorite for high-speed production parts.

Titanium Alloys

Titanium is strong, light, and biocompatible—but challenging to cut.

- Common grades: Grade 2 (commercially pure), Grade 5 (Ti-6Al-4V).

- Properties: Exceptional strength-to-weight ratio, excellent corrosion resistance, low thermal conductivity (causing tool heat concentration).

- Applications: Aerospace fasteners, medical implants, and high-performance automotive parts.

Titanium’s difficulty lies in its heat transfer: without optimized toolpaths, it overheats tools rapidly. Yet, with the right setup, it delivers unmatched performance for critical parts.

Magnesium and Zinc

These two metals are light, fast-cutting, and used when weight reduction is crucial.

- Properties: High machinability, very low density, moderate strength.

- Applications: Consumer electronics, automotive covers, lightweight fixtures.

Both require careful chip control due to their flammability in fine particles—safety measures are essential.

Nickel and High-Temperature Alloys

Inconel, Monel, and Hastelloy represent the high end of CNC machining materials.

- Properties: Maintain strength under extreme heat, corrosion, and pressure.

- Applications: Jet engine components, turbines, and energy equipment.

They’re notoriously hard to machine and demand rigid setups and coated carbide tooling—but they excel where others fail.

Plastic Materials for CNC Machining

Plastic materials expand CNC’s versatility. They’re lighter, often cheaper, and ideal for applications that don’t require metal strength but demand corrosion resistance, insulation, or transparency. In many industries, they replace metals to simplify manufacturing and reduce cost.

ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene)

- Properties: Low cost, good toughness, easy to machine.

- Applications: Prototypes, housings, jigs, and fixtures.

ABS cuts cleanly and is forgiving for beginners, but it’s sensitive to heat deformation during prolonged cutting.

POM / Delrin (Acetal)

- Properties: Excellent dimensional stability, low friction, and high stiffness.

- Applications: Gears, bushings, and mechanical components.

Delrin holds tight tolerances and offers one of the best surface finishes among plastics.

Nylon (PA6, PA66)

- Properties: High impact strength, fatigue resistance, moderate machinability.

- Applications: Bearings, spacers, and structural plastic parts.

However, nylon absorbs moisture, which can slightly alter dimensions over time—an important consideration for precision fits.

PTFE (Teflon)

- Properties: Exceptional chemical resistance, low friction coefficient.

- Applications: Seals, gaskets, and chemical processing components.

Machining PTFE requires sharp tools and low feed rates due to its softness, but it offers unmatched inertness.

PEEK (Polyether Ether Ketone)

- Properties: High temperature resistance (up to 250°C), excellent mechanical strength, biocompatibility.

- Applications: Aerospace parts, surgical implants, high-performance connectors.

PEEK is expensive but irreplaceable for extreme environments.

Polycarbonate (PC)

- Properties: Impact resistant, transparent, stable under moderate heat.

- Applications: Machine guards, optical prototypes, and electronic casings.

Acrylic (PMMA)

- Properties: Excellent optical clarity, good machinability.

- Applications: Display components, lenses, and transparent covers.

Machined acrylic can achieve glass-like finishes with fine tooling.

Specialty and Composite Materials

CNC machining is no longer limited to traditional metals and plastics. Advanced industries often use hybrid materials for specific performance targets.

Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer (CFRP)

- Lightweight, extremely stiff, used in aerospace and motorsport.

- Machining requires diamond-coated tools due to abrasive fibers.

Glass Fiber Reinforced Polymer (GFRP)

- Lower cost alternative to CFRP, good strength and stability.

Engineering Ceramics

- Alumina, zirconia; offer extreme hardness and wear resistance, often used in precision tooling or insulating parts.

Graphite

- Excellent for EDM electrodes and high-temperature fixtures.

Key Material Properties to Consider

After understanding the list of CNC machining materials, the next step is to look deeper into what makes each one perform differently in the machining process. Every material has a unique combination of physical, mechanical, and chemical properties that directly affect how it behaves under cutting forces, heat, and tool movement. Recognizing these differences helps engineers and machinists make smarter choices that balance precision, efficiency, and cost.

Machinability

Machinability defines how easily a material can be cut to meet design specifications. Materials with high machinability generate shorter chips, lower cutting forces, and less tool wear. Aluminum and brass rank among the easiest metals to machine, while titanium and hardened steels sit at the challenging end of the spectrum. In plastics, Delrin (POM) and ABS offer smooth chip removal, while PTFE or nylon can deform under heat.

Good machinability reduces tool cost, improves surface finish, and shortens cycle time—three essential goals in production machining.

Strength and Hardness

Strength and hardness determine a material’s ability to resist deformation and wear. High-strength alloys like titanium or tool steel can handle heavy mechanical loads but demand powerful spindles and rigid setups. Softer materials such as aluminum or ABS machine quickly but may not hold dimensional tolerances under stress. In design, hardness is often balanced with machinability: the harder the material, the more tool wear you must expect.

Dimensional Stability and Thermal Expansion

Dimensional stability refers to a material’s ability to maintain its geometry when exposed to temperature changes during machining. Metals expand under heat; plastics expand even more. This property becomes critical when parts require tight tolerances or when multiple materials interact in assembly.

For example, aluminum expands roughly twice as much as steel for the same temperature rise, while PEEK and nylon may shift further. Knowing the thermal expansion rate helps determine tolerance compensation in both toolpaths and inspection plans.

Corrosion and Chemical Resistance

Resistance to corrosion and chemicals affects both part longevity and appearance. Stainless steels, titanium, and brass naturally resist oxidation and moisture, while untreated carbon steels rust quickly in humid environments. Plastics such as PTFE and PEEK offer near-total chemical inertness, making them ideal for laboratory or chemical plant use.

Selecting the right level of corrosion resistance avoids unnecessary surface treatments and long-term maintenance issues.

Surface Finish Potential

Surface finish potential describes how smooth and accurate a surface can be achieved after machining. Materials with uniform grain structures—like aluminum, brass, or POM—produce clean finishes with minimal polishing. On the other hand, materials that are fibrous, brittle, or soft, such as CFRP or PTFE, tend to show rougher textures or require secondary finishing.

Surface quality affects not just appearance but also sealing performance, friction, and component fit.

Density and Weight

Density influences both part weight and cutting dynamics. Lightweight materials such as aluminum, magnesium, and engineering plastics reduce mass and improve energy efficiency in motion systems. Dense materials like steel or copper offer rigidity and vibration damping but increase cutting forces.

For aerospace and automotive industries, balancing weight and stiffness is a key design factor; machinists must consider both mechanical and machining implications when choosing material density.

Cost and Availability

Material cost goes beyond the price per kilogram. It includes the stock form, waste ratio, local availability, and the tooling time needed to reach final geometry. Common materials such as 6061 aluminum or 1045 steel are available worldwide, while titanium and PEEK can multiply the cost of both raw stock and tooling.

Evaluating material cost also involves calculating cost per part, including cycle time, tool wear, and scrap rate. Availability and consistency of supply often determine whether a material is feasible for large production runs.

Summary of Key Properties

Each property—machinability, strength, stability, resistance, finish potential, density, and cost—interacts with the others. A material that excels in one area may compromise another. High machinability may mean lower strength; excellent corrosion resistance might come at a higher cost.

Understanding these trade-offs is the foundation for selecting the right CNC machining material. The next section will organize these factors into a clear framework to guide practical material choice in real manufacturing projects.

How to Choose the Right CNC Machining Material

Selecting the right material is more than comparing mechanical charts—it’s about understanding the complete balance between design goals, machinability, and economic efficiency. In my years managing CNC production lines, I’ve seen that material choice determines not only how easily a part is made, but also how long it performs in the field. The following framework is the method I recommend for every engineer or buyer evaluating CNC Machining Materials.

Define Your Project Requirements

Material selection always begins with understanding the part itself. Start by defining the function, the mechanical loads it must endure, and the environment it will operate in. Ask these key questions:

- What stress or vibration will the part face during operation?

- What tolerance levels must be maintained under thermal or mechanical load?

- Will the part be exposed to moisture, heat, or chemicals?

- Is this a prototype or a high-volume production component?

Aerospace parts, for instance, prioritize strength-to-weight ratio; automotive parts focus on cost and durability; medical parts demand biocompatibility. By clearly defining these parameters, you establish the boundaries within which material choices can be made logically—not emotionally.

Match Machinability with Performance

Once the design requirements are set, the next step is to match material machinability with performance needs. Every material interacts differently with cutting tools, spindle speed, and coolant.

Highly machinable materials like aluminum or brass allow fast cycle times and fine finishes but may lack stiffness or temperature resistance. Harder materials such as titanium and stainless steel offer superior mechanical performance but increase machining time and tool wear.

When deciding, consider:

- Machinability rating (based on the 1212 Steel reference scale).

- Tool wear and cutting temperature.

- Feeds and speeds compatible with your equipment.

- Surface finish requirements after machining.

Selecting a material with appropriate machinability avoids production bottlenecks and ensures that your design can be manufactured within schedule and budget.

Compare Cost and Production Efficiency

Choosing the right material always involves cost trade-offs. The “best” technical material may not be the most economical when total manufacturing cost is considered. Evaluate each candidate using cost per finished part, not just raw material price.

Cost-per-part = Material cost + Cycle time + Tooling wear + Scrap loss

For example, aluminum 6061 may cost less to machine and polish than stainless steel 304, even though the raw metal price difference is small. Similarly, brass often machines so quickly that its higher material price is offset by shorter cycle times.

Key points to compare include:

- Material price per kilogram or per block/bar.

- Machining time and spindle load.

- Tool life expectancy for that material.

- Scrap and rework rates.

- Post-processing requirements (anodizing, polishing, passivation).

In mass production, these small factors accumulate to major cost differences, which can directly impact profit margins and delivery reliability.

Validate Your Material Choice Through Testing

Even the best theoretical decision must be verified through practice. Always validate your chosen material before committing to full production.

Start by reviewing the manufacturer’s material data sheet (MDS) for tensile strength, hardness, and thermal properties. Then, perform pilot machining tests using production tools and cutting parameters to confirm dimensional stability, surface finish, and chip formation.

Evaluate the following outcomes:

- Tool wear and heat generation.

- Surface roughness and burr formation.

- Dimensional drift or warping during cooling.

- Consistency between multiple stock batches.

For critical applications, conduct limited batch runs or cross-test alternative suppliers to verify quality consistency. It’s also wise to record all findings—cutting speeds, feed rates, and observed tool behavior—to build an internal database for future reference. Over time, this knowledge base becomes one of your strongest competitive advantages.

Integrating Data with Experience

Material selection isn’t purely analytical—it’s also experiential. Data provides guidance, but hands-on machining confirms feasibility. The best decisions come from combining the two: using data sheets to narrow options, then validating through small-scale trials.

Application Cases of CNC Machining Materials

Every industry approaches CNC machining with different performance priorities. The same aluminum bar or plastic billet can serve entirely different functions depending on the design goals, environmental demands, and production constraints. By understanding which materials are commonly used across industries, we can better connect theoretical selection criteria with real-world results.

Aerospace Industry

The aerospace field demands a balance of low weight, high strength, and extreme reliability. Components are often exposed to vibration, pressure, and thermal variation, which restricts the range of usable materials.

- Common materials: Aluminum 7075, Titanium Grade 5, Stainless Steel 17-4PH, PEEK.

- Key reasons for selection:

- High strength-to-weight ratio for structural integrity.

- Dimensional stability under temperature change.

- Resistance to corrosion and fatigue.

- Typical applications: Airframe brackets, turbine housings, landing gear parts, and aerospace connectors.

Aluminum 7075 remains the go-to material for structural parts due to its combination of machinability and stiffness. Titanium Grade 5, though difficult to machine, is chosen for critical load-bearing components where weight reduction is essential.

Automotive Industry

In automotive manufacturing, efficiency and scalability are critical. The materials must balance machinability, strength, and cost across large production runs.

- Common materials: Mild Steel 1045, Aluminum 6061, Cast Iron, Brass.

- Key reasons for selection:

- Cost-effective mass production.

- High wear resistance for drivetrain and engine parts.

- Easy surface finishing for aesthetic components.

- Typical applications: Engine blocks, brackets, shafts, bushings, and transmission components.

For example, Aluminum 6061 is often selected for engine housings or brackets, where lightweight design contributes directly to fuel efficiency. Steel and cast iron, on the other hand, are reserved for components exposed to friction and heat.

Medical Industry

Medical manufacturing is one of the most demanding fields for CNC machining materials. The parts must be biocompatible, corrosion-resistant, and dimensionally precise.

- Common materials: Titanium Grade 2 and 5, Stainless Steel 316L, PEEK, PTFE.

- Key reasons for selection:

- Biocompatibility with human tissue and fluids.

- Smooth surface finish for sterilization.

- Dimensional stability during sterilization and use.

- Typical applications: Surgical instruments, orthopedic implants, dental implants, and precision housings.

Titanium and PEEK are particularly favored because they combine mechanical performance with long-term biological safety. Stainless Steel 316L provides a cost-effective solution for reusable surgical tools.

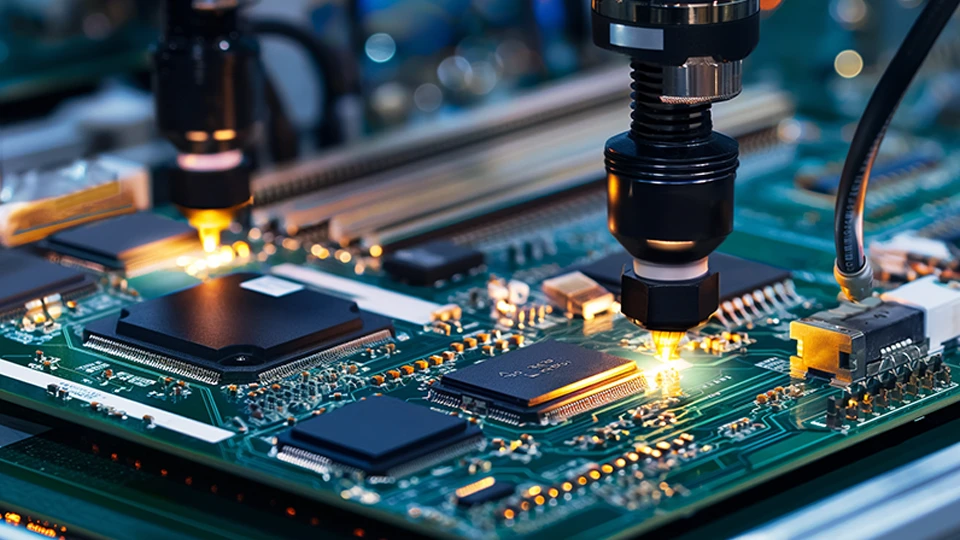

Electronics and Electrical Components

This sector emphasizes precision, conductivity, and insulation. Materials must allow small, detailed machining while providing reliable electrical properties.

- Common materials: Brass, Copper, Aluminum, Polycarbonate (PC), POM.

- Key reasons for selection:

- Excellent conductivity for electrical contacts.

- Dimensional stability for connectors and housings.

- Smooth machining for micro-features.

- Typical applications: Electrical connectors, switch housings, heat sinks, optical mounts.

Brass and copper dominate this category for their machinability and conductivity, while plastics like POM and PC are used where electrical insulation is necessary.

Industrial Equipment and Tooling

General industrial machinery and tooling require durability and cost efficiency. Components must endure repetitive mechanical loads and resist wear.

- Common materials: Alloy Steel 4140, Stainless Steel 304, Aluminum 6061, Engineering Ceramics.

- Key reasons for selection:

- Strength and impact resistance.

- Compatibility with surface treatments (nitriding, plating).

- Thermal and chemical stability for tool components.

- Typical applications: Fixtures, clamps, housings, and custom jigs.

Alloy steels offer the toughness and fatigue resistance needed for repetitive use, while aluminum helps reduce total fixture weight without compromising rigidity.

Comparative Overview

| Industry | Typical Materials | Core Priorities | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerospace | Aluminum 7075, Titanium, PEEK | Weight reduction, fatigue resistance | Brackets, housings, fasteners |

| Automotive | Steel, Aluminum 6061, Brass | Cost, strength, mass production | Shafts, brackets, housings |

| Medical | Titanium, Stainless 316L, PEEK | Biocompatibility, sterilization | Implants, surgical tools |

| Electronics | Brass, Copper, PC | Conductivity, precision | Connectors, heat sinks |

| Industrial | Alloy Steel, Aluminum | Strength, wear resistance | Jigs, fixtures, tooling |

This comparison shows how each sector prioritizes specific material attributes—weight, strength, cost, or corrosion resistance—based on function. Recognizing these trade-offs helps engineers and procurement teams justify material decisions and align them with end-use requirements.

Conclusion

Behind every precise CNC part lies two forms of understanding — the material itself, and the logic behind choosing it. Metals, plastics, and composites all respond differently to heat, force, and time; learning their behavior is how engineers gain control over tolerance, finish, and cost. Once that understanding is built, selection becomes strategic rather than instinctive: define the function, environment, and accuracy required; evaluate machinability and availability; compare the true cost per part; then test and confirm before scaling up. This is how informed material choice turns uncertainty into consistency and experience into repeatable precision.

That same principle shapes how we work at Rosnok. The machines we build must master every material our customers use — from lightweight aluminum and engineering plastics to tough steels and titanium alloys. Each lathe or machining center is designed to deliver stable performance across that range, because real manufacturing demands flexibility and control. The lessons we learn from cutting these materials feed directly back into how we engineer our machines, ensuring that precision isn’t just expected from our tools — it’s built into them.