Key Functions of a Machine Foundation

A machine foundation is more than a concrete base. It directly affects machine stability, accuracy, and long-term performance. In practice, foundation quality plays a critical role even when the machine itself is well designed.

Supporting Static and Dynamic Loads

The primary role of a machine foundation is to support both static and dynamic loads. Static loads include the machine’s own weight, fixtures, and workpieces. Dynamic loads come from cutting forces, acceleration, deceleration, and intermittent machining operations.

If loads are not transferred evenly to the ground, the foundation may deform or settle unevenly. Even small movements at the foundation level can affect machine alignment and machining stability. For this reason, load support is not just about strength, but about maintaining consistent support under changing working conditions.

Controlling Vibration and Damping

During machining, vibration is unavoidable. It may come from cutting processes, rotating components, or external sources. The foundation helps control how these vibrations behave within the machine system.

A well-designed foundation limits vibration amplitudes and reduces the risk of resonance. Mass, stiffness, and damping all influence how vibration is absorbed or transmitted. When foundation dynamics are poorly matched to the machine, vibration can increase, leading to unstable cutting and reduced surface quality.

Maintaining Geometric Accuracy Over Time

Initial machine alignment can usually be achieved during installation. The greater challenge is keeping that alignment over long-term operation. The foundation acts as the geometric reference for the entire machine.

Gradual settlement, deformation, or environmental effects can cause slow accuracy drift. These changes are often difficult to correct through calibration alone. A stable foundation helps preserve machine geometry, ensuring consistent accuracy and repeatability throughout the machine’s service life.

Types of Machine Foundations

Machine foundations take different structural forms depending on machine characteristics, ground conditions, and performance requirements. Each foundation type represents a different balance between mass, stiffness, vibration behavior, and construction complexity.

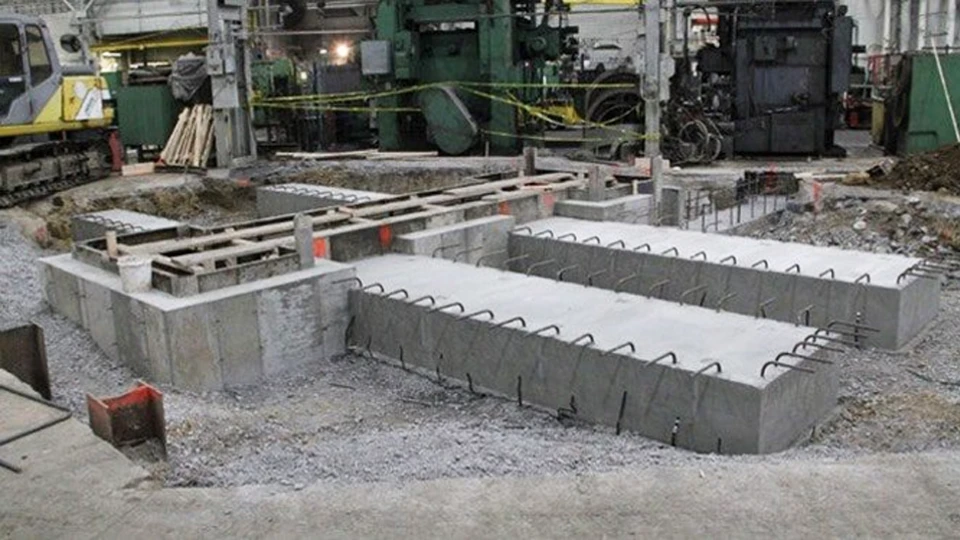

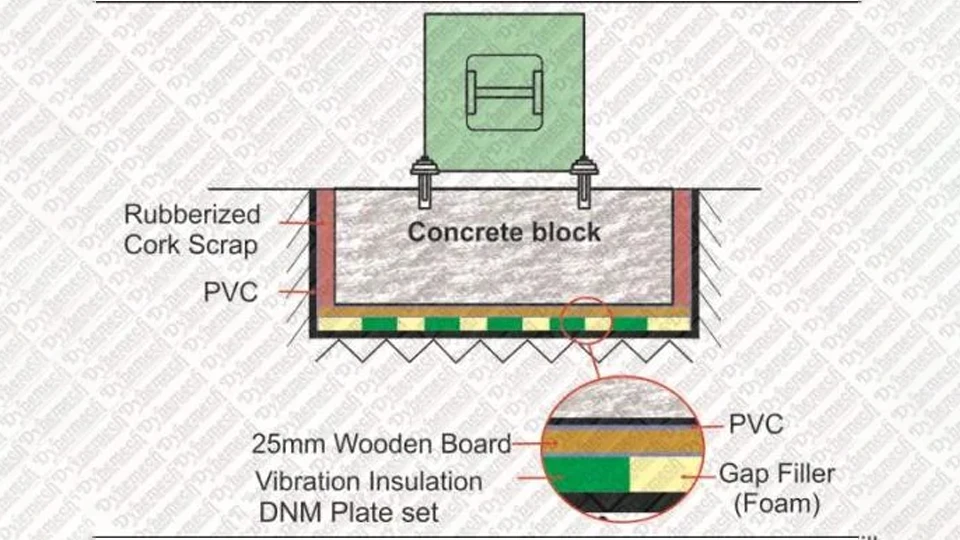

Mass Concrete (Block) Foundations

Mass concrete foundations, often called block foundations, rely primarily on weight and rigidity. Their large mass helps resist movement and reduces the influence of cutting forces on the machine.

This type is commonly used for heavy machine tools and equipment that generate significant low-frequency forces. While block foundations are simple and robust, their performance depends heavily on soil conditions and proper sizing. Excessive mass alone does not guarantee good vibration behavior, especially for machines sensitive to higher-frequency excitation.

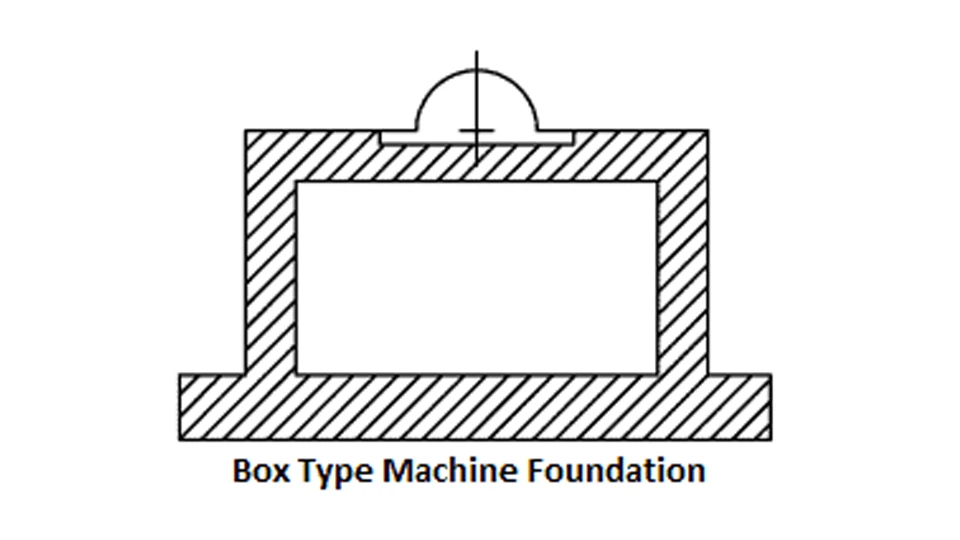

Box-Type Foundations

Box-type foundations use a hollow or partially hollow structure to achieve high stiffness with more efficient material usage. Compared with solid blocks, they can provide similar rigidity while reducing overall concrete volume.

These foundations are often applied to medium and large CNC machines where both structural stiffness and construction efficiency are important. However, box-type designs require careful engineering and execution. Poor detailing or uneven stiffness distribution can reduce their effectiveness.

Pile Foundations

Pile foundations are used when surface soil cannot provide sufficient bearing capacity or stability. Loads are transferred through piles to deeper, more stable soil layers.

This approach addresses ground limitations rather than machine characteristics. While pile foundations make installation possible in challenging locations, differences in pile stiffness or improper layout can introduce uneven support if not carefully controlled.

Isolated Machine Foundations

Isolated foundations are structurally separated from the surrounding building floor or structure. The goal is to limit vibration transmission between the machine and its environment.

This type is often used for vibration-sensitive machines or facilities with multiple machines operating nearby. Isolation can be effective, but excessive compliance may reduce overall system stiffness and negatively affect machining stability.

Foundations Integrated with Building Structures

In some installations, machine foundations are integrated directly into the building floor or structural slab. This approach is typically used for lighter machines or applications with modest performance requirements.

Integrated foundations are cost-effective and simple to construct, but their performance is closely tied to the building structure itself. Floor stiffness, reinforcement layout, and external loads all influence machine behavior, limiting suitability for high-precision or heavy-duty applications.

Machine Foundation Design Principles

Designing a machine foundation is not about following a fixed template. It is about matching the foundation’s structural behavior to the machine, the operating conditions, and the site. Effective foundation design focuses on load behavior, stiffness distribution, ground conditions, and vibration control.

Load Analysis and Machine Characteristics

Foundation design starts with understanding the machine itself. Different machines generate different load patterns depending on mass, spindle speed, cutting forces, and motion dynamics.

Static loads define the baseline bearing requirement, while dynamic loads determine how the foundation responds during operation. Machines with intermittent cutting, high acceleration, or frequent direction changes place greater demands on foundation stiffness and stability. Ignoring these characteristics often leads to foundations that are strong enough on paper but unstable in real operation.

Foundation Mass, Rigidity, and Geometry

Mass and rigidity are closely related but not interchangeable. Increasing mass can help reduce movement, but mass alone does not guarantee good performance. The geometry of the foundation determines how stiffness is distributed and how loads are transferred to the ground.

A well-designed foundation uses geometry to control deformation, ensuring that the machine is supported uniformly. Poor stiffness distribution can cause localized deflection, even when overall foundation mass appears sufficient.

Soil Conditions and Ground Preparation

No foundation design can be separated from ground conditions. Soil bearing capacity, stiffness, and settlement behavior directly influence foundation performance.

If soil conditions are weak or inconsistent, foundation behavior will be governed by ground response rather than structural design. Proper ground preparation, compaction, or reinforcement is often more critical than adding concrete to the foundation itself.

Vibration Isolation vs. Rigid Mounting

Foundation design often involves a trade-off between isolation and rigidity. Rigid foundations favor stability and load transfer, while isolation aims to reduce vibration transmission.

The appropriate approach depends on machine sensitivity, operating speed, and surrounding conditions. Over-isolation can reduce stiffness and harm machining stability, while insufficient isolation may allow vibration to propagate. Effective design balances these effects rather than maximizing one at the expense of the other.

Common Machine Foundation Mistakes

Many machine foundation problems are not caused by a lack of concrete or strength, but by incorrect assumptions made during planning and installation. These mistakes often remain hidden at the beginning and only become visible after accuracy loss, vibration issues, or repeated adjustments appear. Recognizing these common errors helps avoid costly rework and long-term performance problems.

The “More Concrete Is Better” Fallacy

One of the most common mistakes is treating the machine foundation as nothing more than a concrete block. In this mindset, increasing concrete volume is assumed to improve machine stability.

In practice, foundation performance depends on stiffness distribution, geometry, and interaction with the ground—not mass alone. Excessive concrete without proper structural behavior may reduce visible movement, yet still allow deformation or unfavorable vibration response. A typical symptom is persistent accuracy drift despite repeated leveling or alignment attempts.

Ignoring Dynamic Machine Behavior

Another frequent error is designing the foundation based only on static loads. Machine tools generate dynamic forces during cutting, acceleration, deceleration, and tool changes.

When dynamic behavior is ignored, the foundation may appear sufficient on drawings but perform poorly in operation. Common symptoms include unstable cutting during finishing operations, unexpected surface roughness variation, or increased servo load as control systems attempt to compensate for vibration. Foundations must account for how machines behave while running, not just while standing still.

Over-Isolating High-Precision Machines

Vibration isolation is often viewed as a universal solution for precision problems. As a result, machines are sometimes mounted on isolation systems without considering the effect on overall stiffness.

Excessive isolation can reduce system rigidity and compromise machine positioning accuracy. In practice, this may appear as slow response, reduced repeatability, or sensitivity to cutting parameter changes. Isolation should be applied selectively and balanced against the need for structural stability.

The “Copy-Paste” Trap in Foundation Design

Reusing a foundation design from another machine or project is a common but risky practice. Even machines that look similar can differ significantly in mass distribution, operating speed, and dynamic response.

A foundation that performs well in one installation may cause problems in another, especially when soil conditions or production requirements change. Typical symptoms include unexpected vibration behavior or alignment issues that were not present in the original installation. Always treat foundation design as machine- and site-specific, rather than reusable by default.

How to Evaluate an Existing Machine Foundation

Evaluating an existing machine foundation is about determining whether the foundation is supporting the machine as intended under real operating conditions. This process is especially important when machines show performance issues that cannot be explained by tooling, parameters, or control settings alone. A proper evaluation focuses on observable behavior rather than assumptions about how the foundation was originally built.

Visual and Geometric Checks

The first step in evaluation is a visual and geometric inspection. Cracks, uneven surfaces, or visible separation between the machine and foundation may indicate structural or settlement-related issues. Changes in machine level or alignment over time are also important signals.

Repeated leveling adjustments that fail to hold are often not installation errors, but signs that the foundation or ground is moving. These checks do not confirm root causes, but they help determine whether the foundation should be investigated further.

Observing Vibration Behavior During Operation

Vibration behavior under operating conditions provides valuable insight into foundation performance. Unusual vibration patterns, sensitivity to cutting parameters, or chatter appearing only in specific speed ranges may indicate unfavorable interaction between the machine and its foundation.

It is important to observe vibration while the machine is cutting, not just while running idle. Problems that only appear during machining often point to dynamic issues rather than static structural defects.

When Reinforcement Is Possible

Not all foundation problems require complete replacement. In some cases, reinforcement or modification may improve performance. This is more likely when issues are localized, or when the foundation structure itself is sound but limited by stiffness or support conditions.

However, reinforcement decisions should be based on clear evidence. Attempting reinforcement without understanding the underlying behavior may mask symptoms rather than resolve them.

When Redesign Is Unavoidable

In some situations, foundation redesign is the only practical solution. This typically occurs when problems are linked to fundamental limitations such as inadequate soil conditions, incompatible foundation type, or severe dynamic mismatch with the machine.

If repeated downtime, scrap, and corrective work begin to approach the cost of rebuilding the foundation, or if soil settlement continues over time, redesign should be seriously considered.

Conclusion

A machine foundation is often overlooked because it sits quietly beneath the machine, unseen and unchanged for years. Yet throughout this article, one message should be clear: foundation behavior directly shapes machine stability, accuracy, and long-term performance. From load transfer and vibration control to soil interaction and real-world failure modes, the foundation is an active part of the machine system. Many persistent performance issues traced to machines ultimately begin at the foundation level.

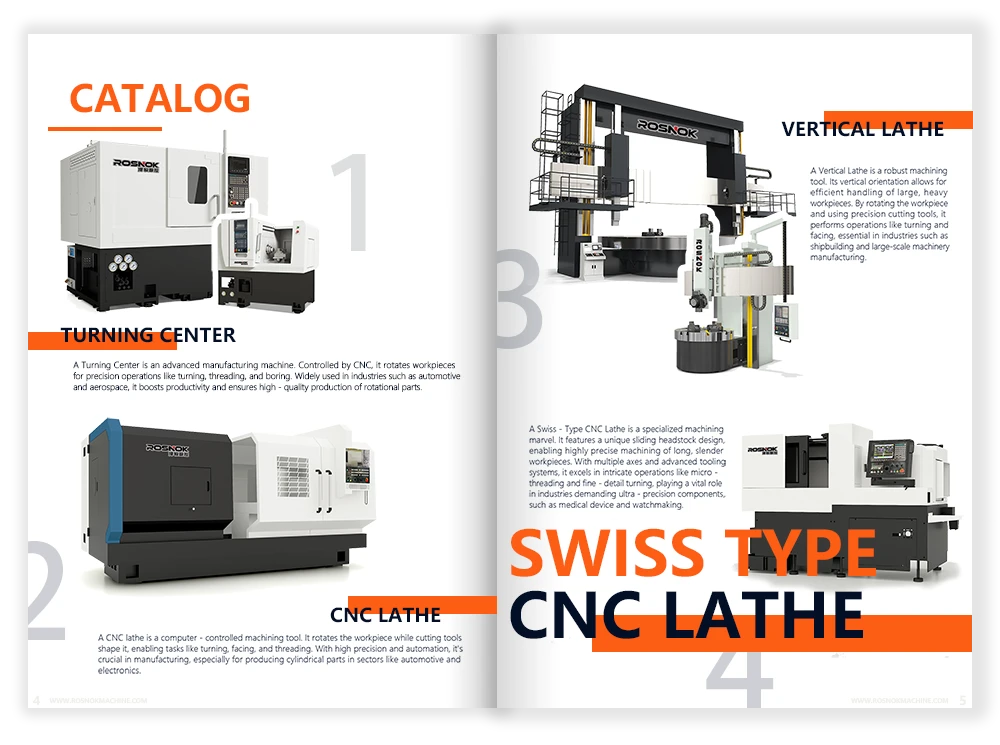

As this perspective becomes clearer, it also explains why machine builders with deep application experience place strong emphasis on real-world installation conditions. Companies like Rosnok, focused on the design and manufacture of CNC lathes and machining centers, approach machine performance as a system-level outcome rather than a standalone specification. By accounting for how machines interact with their foundations, operating environments, and long-term use conditions, such manufacturers aim to deliver equipment that performs reliably not only in theory, but across the full service life on the shop floor.