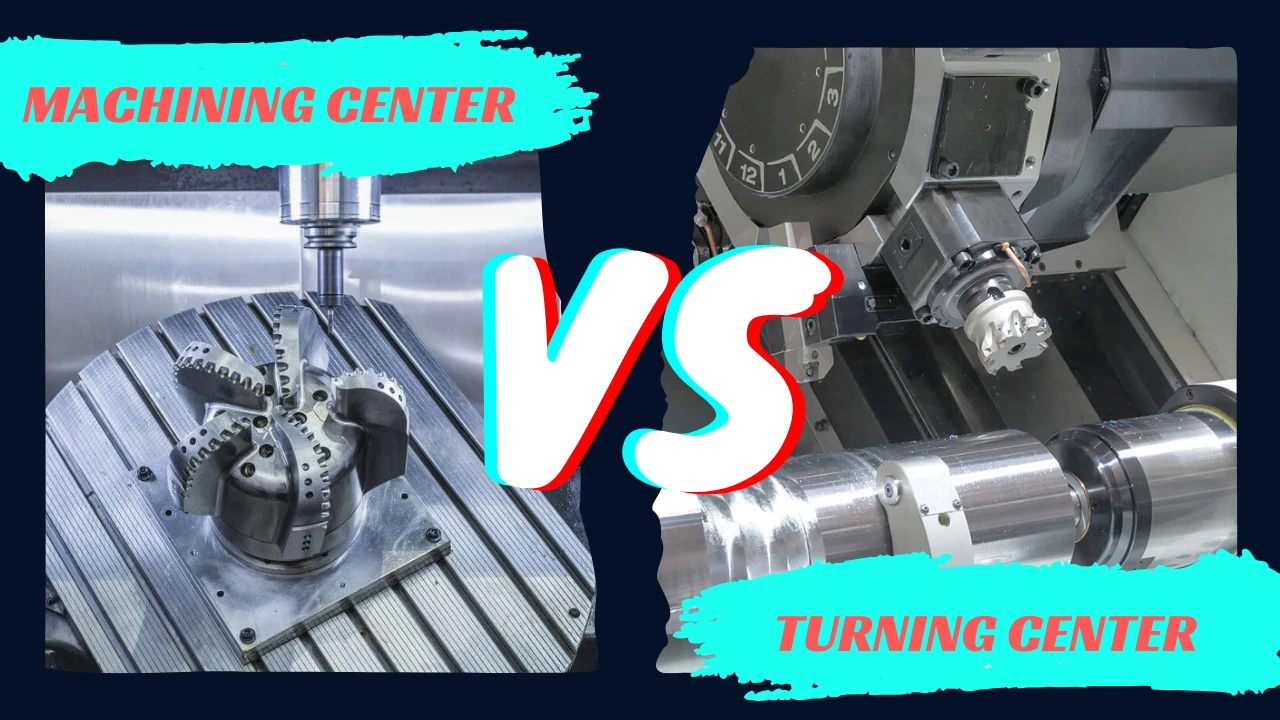

The key difference between a machining center and a turning center lies in their machining method and application. A machining center uses rotating tools to perform milling, drilling, and tapping operations on the workpiece—ideal for multi‑surface and complex 3D parts. A turning center, however, rotates the workpiece when using fixed tools for turning, but stops the spindle when using live tooling, allowing the rotating tool to machine features on the part, making it optimal for cylindrical and shaft‑type components. Machining centers deliver versatile multi‑process precision, while turning centers excel in efficient round‑part production.

What Is a Machining Center?

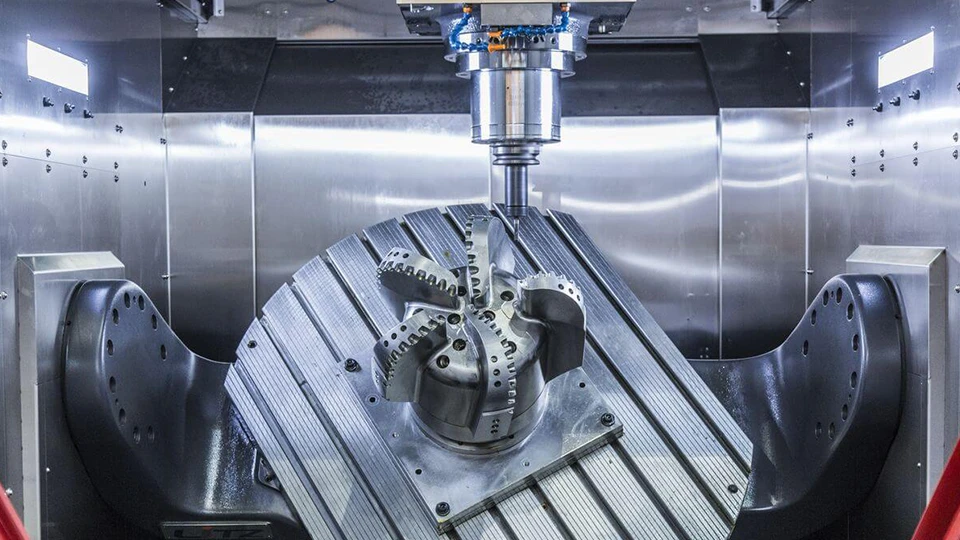

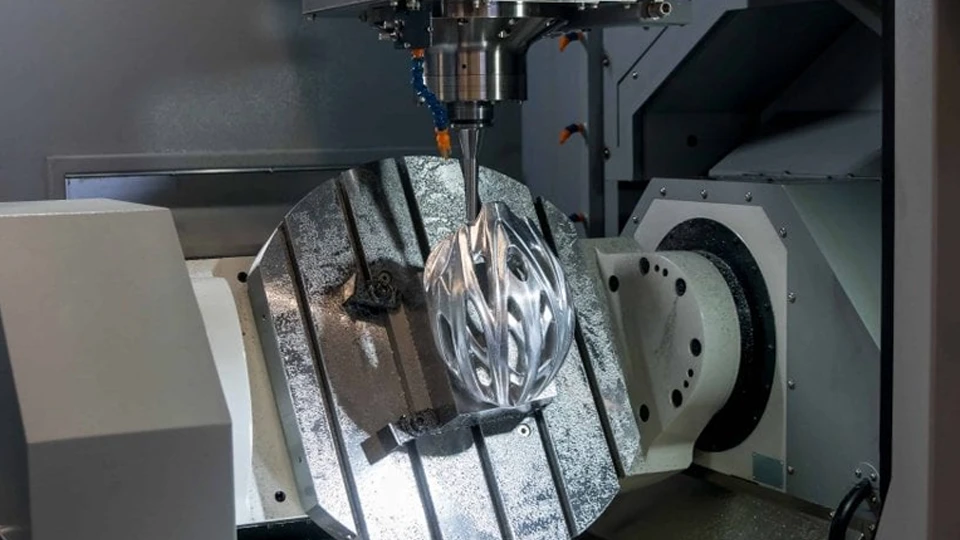

A machining center is a type of CNC machine tool designed to perform a variety of cutting operations using a rotating tool, rather than rotating the workpiece. These machines operate through computer-controlled, multi-axis movements, allowing precise tool paths across complex surfaces. The rotating cutting tool interacts with a stationary or dynamically positioned workpiece, enabling high-precision shaping, contouring, and finishing.

Unlike basic milling machines, machining centers are equipped with automated systems that support multiple processes—such as milling, drilling, boring, tapping, and more—within a single setup. This integration improves machining accuracy, reduces manual intervention, and significantly shortens production time. Advanced models offer multi-axis synchronization, which is especially useful for producing intricate 3D surfaces and multi-face geometries.

Machining centers typically feature a tool magazine, an automatic tool changer (ATC), and servo-driven axis control. Depending on the spindle orientation, they are classified into vertical machining centers (VMCs) and horizontal machining centers (HMCs). High-end configurations may include five-axis or multi-tasking setups, enabling full-surface access and reducing the number of setups needed. These capabilities make machining centers ideal for precision-driven industries such as aerospace, automotive, and mold manufacturing.

What Is a Turning Center?

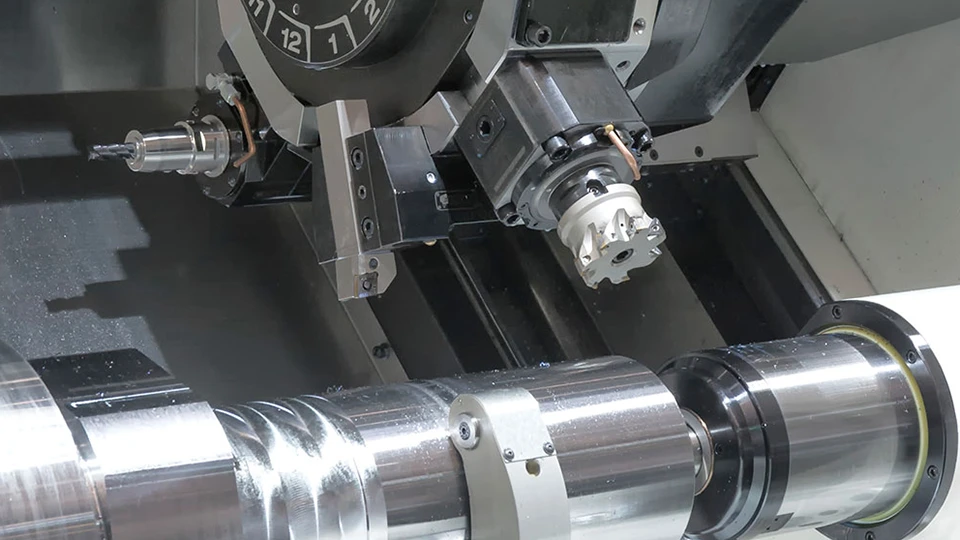

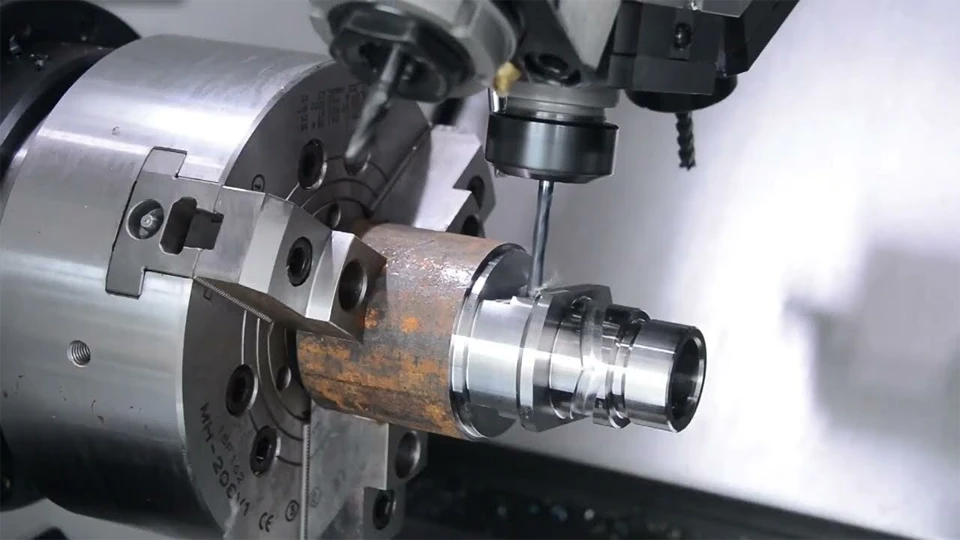

A turning center is a type of CNC machine tool primarily designed for machining rotational parts through the process of turning, where the workpiece itself rotates against a stationary cutting tool. This configuration allows for highly efficient and accurate shaping of cylindrical surfaces, grooves, threads, and tapers along the workpiece’s outer profile.

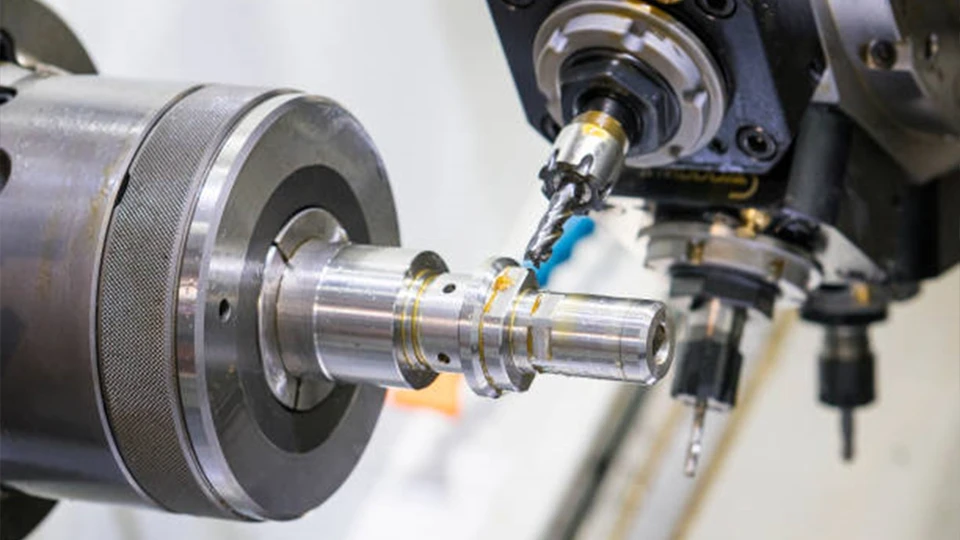

Modern turning centers are far more advanced than traditional lathes. In addition to standard turning capabilities, most turning centers are equipped with live tooling—motor-driven cutting tools that enable secondary operations such as drilling, milling, and tapping on the face or sides of the part. When live tooling is used, the spindle holding the workpiece typically stops rotating, allowing the powered tool to perform the operation. This multi-functionality significantly reduces the need for additional setups on other machines.

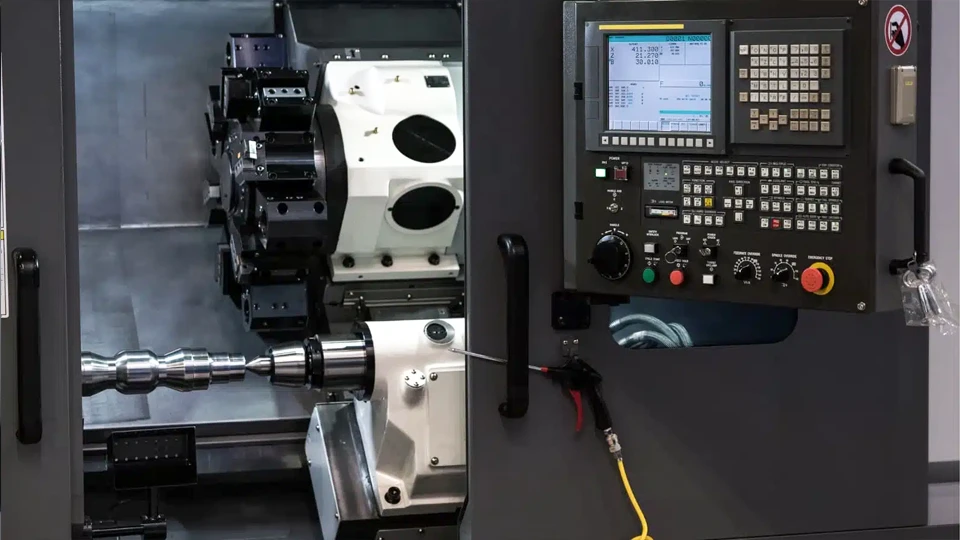

Turning centers generally include a servo or electric turret for tool indexing, tool changing, and live tooling integration, and may be configured with an optional sub-spindle (dual-spindle configuration) or Y-axis to enhance machining flexibility. Some models also feature C-axis rotation for contouring and positioning during complex part production. With these configurations, turning centers are capable of handling more complex machining tasks in a single setup.

Key Differences Between Machining Centers and Turning Centers

While machining centers and turning centers are both common types of modern metalworking equipment, they are fundamentally different in their construction, cutting strategies, and operational strengths. Understanding these differences is essential for manufacturers and engineers tasked with selecting the right equipment for specific production goals. The following sections break down the key aspects that set these two machine types apart—from machining methodology to automation, part compatibility, and long-term operational costs.

1. Machining Capabilities and Methodology

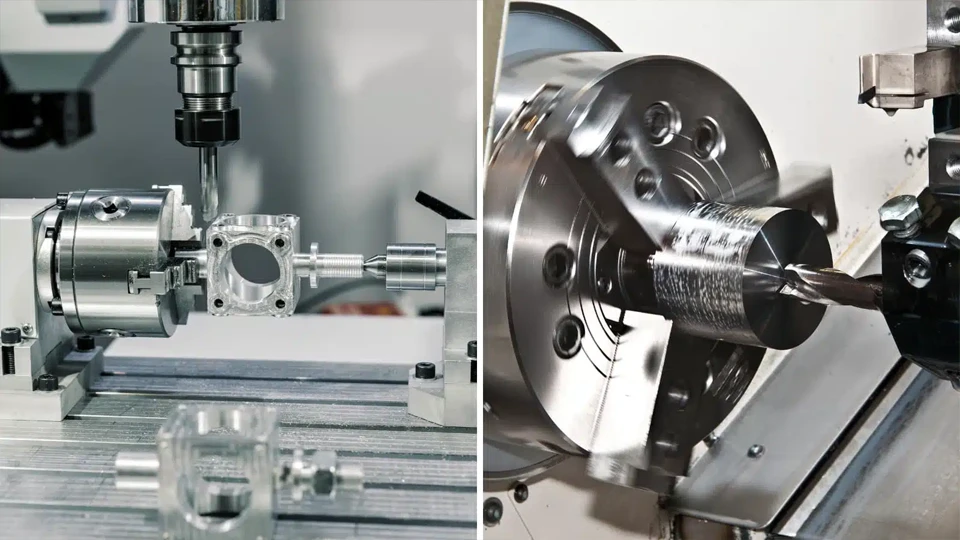

The primary distinction between machining centers and turning centers lies in how material is removed from the workpiece. Machining centers rely on rotating cutting tools to perform a variety of operations—such as milling, drilling, tapping, and boring—while the workpiece remains stationary or is dynamically positioned across multiple axes. This configuration allows simultaneous multi-surface machining and makes machining centers ideal for producing parts with complex 3D geometries, intersecting features, and tight dimensional tolerances.

In contrast, turning centers are based on the rotation of the workpiece itself, using fixed tools to perform turning operations along the outer and inner diameters. However, modern turning centers often come equipped with live tooling, enabling them to go beyond simple turning. With live tooling and auxiliary axes like Y and C, turning centers can perform basic milling, drilling, and tapping—typically on the end face or cross-section of rotational parts. For example, a turning center can tap bolt holes on the face of a wheel hub or mill cross-holes in a stepped shaft—tasks traditionally reserved for milling machines.

Despite this versatility, turning centers have inherent limitations in tool orientation, tool reach, and surface accessibility. Their non-continuous cutting paths and restricted axis movement limit their ability to machine complex curves, multi-angle surfaces, or non-revolving profiles. Machining centers, with true multi-axis interpolation, excel at producing freeform surfaces, tight inside corners, and deep cavities in a single setup with superior precision. As a result, while turning centers are well-suited for parts with rotational symmetry and moderate secondary features, machining centers remain the better choice for intricate and multi-process components.

2. Axis Configuration and Motion Control

One of the most fundamental differences between machining centers and turning centers lies in their axis structure and motion control system. Machining centers are typically equipped with three to five axes, which can be linearly or rotationally controlled. In a standard 3-axis setup, the cutting tool moves along the X, Y, and Z axes to approach the workpiece from different angles. More advanced configurations include fourth (A-axis) and fifth (B-axis) rotational movements, allowing the tool or table to tilt and rotate—enabling true multi-face and freeform surface machining in a single setup.

Turning centers, in contrast, are built around a rotating spindle that spins the workpiece, while the cutting tools are mounted on a turret that moves along linear axes, typically X and Z. However, modern turning centers often integrate additional motion capabilities to expand their versatility. For example, many high-end turning centers now feature a Y-axis, which enables off-center milling and drilling operations, and a C-axis, which allows for indexed or interpolated rotation of the workpiece during milling. Some machines also include dual spindles, enabling front and back machining without manual repositioning.

The distinction in motion complexity also affects machining flexibility. Machining centers, especially five-axis models, can follow continuous 3D toolpaths, making them suitable for sculpted surfaces and intricate contours. Turning centers, though capable of certain interpolated movements, are more limited in simultaneous multi-axis control and are better suited for parts with rotational symmetry and localized features. Overall, machining centers offer superior spatial freedom and interpolation, while turning centers balance rotational precision with targeted tool movement for cylindrical part production.

3. Tooling and Automation Systems

Tooling and automation represent another major distinction between machining centers and turning centers, directly affecting production efficiency, process integration, and equipment versatility. Machining centers typically feature an automatic tool changer (ATC) system, which draws tools from a multi-position tool magazine. Depending on the machine size and configuration, these magazines can hold anywhere from 12 to over 100 tools, allowing for rapid, automated switching between operations like rough milling, finishing, drilling, and tapping. This setup enables continuous multi-step machining without manual intervention and supports complex part geometries with varied toolpath requirements.

Turning centers, on the other hand, primarily use a turret system for tool holding and indexing. These turrets, which can be servo-driven or electrically actuated, generally hold 8 to 12 stations and rotate to bring the desired tool into position. While traditional turning tools are fixed, many modern turning centers integrate live tooling stations on the turret. These allow powered tools to perform axial and radial machining functions, significantly expanding the machine’s capabilities beyond simple turning. However, compared to machining centers, the number of tools available at any one time is usually more limited, which can constrain flexibility for complex or multi-feature parts.

Automation also differs between the two. Machining centers often support additional automation features such as tool life monitoring, broken tool detection, and programmable coolant systems. Advanced systems may include pallet changers, robotic loading, and in-process measurement for closed-loop feedback. Turning centers also offer automation options, particularly in production environments requiring high throughput, such as bar feeders, parts catchers, and spindle transfer systems. The choice between the two ultimately depends on the level of automation required and the complexity of operations to be integrated within a single machine setup.

4. Workpiece Suitability and Typical Parts

Machining centers and turning centers are engineered for fundamentally different categories of workpieces, with their respective mechanical configurations and cutting dynamics making them better suited for specific types of parts.

Machining centers excel in producing components that require complex geometries, multiple surface features, and high positional accuracy. These machines are particularly effective for parts with intersecting holes, angled faces, deep cavities, or freeform surfaces that must be machined from several directions. Typical applications include structural housings, engine blocks, precision brackets, and tooling components—often made from aluminum, steel, or titanium. The ability to integrate multi-face operations in one setup makes machining centers ideal for parts where tolerance stacking and fixture complexity would otherwise pose challenges.

Turning centers, by contrast, are best suited for rotationally symmetric parts—such as shafts, bushings, rings, flanges, and threaded components. The core strength of a turning center lies in its ability to maintain high concentricity and dimensional consistency on cylindrical features, making it the preferred choice for high-throughput manufacturing of round parts. With the addition of live tooling, turning centers can also machine features on the part’s face or cross-section, such as end-face holes, grooves, or flats. This makes them a practical solution for moderately complex parts that retain a primary turning profile but require limited secondary operations.

5. Production Efficiency and Precision

Machining centers and turning centers differ not only in machining methods but also in their approach to production efficiency and achievable precision levels, which are critical factors in manufacturing decision-making.

Machining centers are designed for operations that require high dimensional accuracy, surface quality, and tight tolerance control across multiple features. These machines are capable of maintaining precise tool positioning through servo-driven axes, advanced interpolation algorithms, and in some cases, thermal compensation systems. Especially in multi-axis machining, machining centers can achieve superior geometric tolerances and surface finishes on complex components. However, due to toolpath complexity and multi-step operations, cycle times are generally longer—making them better suited for parts where precision outweighs raw throughput.

Turning centers, in contrast, offer exceptional productivity for parts with rotational symmetry. Their simplicity of motion—spinning the workpiece and advancing the tool—allows for extremely efficient material removal, short cycle times, and rapid tool indexing. This makes them highly effective for medium- to high-volume production runs. When combined with bar feeders and automatic part unloading, turning centers can operate continuously with minimal human intervention, achieving high levels of throughput.

In terms of accuracy, turning centers provide excellent results in terms of roundness, concentricity, and axial alignment—especially important in automotive shafts, bushings, and bearing components. However, when using live tooling to perform non-turning operations such as milling or drilling, their precision may decline slightly due to structural limitations and lower tool rigidity compared to machining centers. This is particularly evident when machining off-center features or when fine-tolerance flat surfaces are required.

Ultimately, machining centers excel in producing parts that demand high surface finish, multi-directional tolerances, and complex geometry, even at the cost of longer cycle times. Turning centers dominate in high-speed, high-volume applications where rotational parts are the primary product and tight concentricity is the main quality criterion.

6. Cost, Space, and Maintenance

The overall investment and operational footprint of machining centers and turning centers can vary significantly, impacting equipment selection for both large factories and smaller workshops. Machining centers, particularly multi-axis and high-speed models, generally have a higher initial cost due to their advanced control systems, tool changers, and multi-axis mechanics. In contrast, turning centers—especially standard 2-axis configurations—are typically more cost-effective upfront, though prices increase with the addition of live tooling, Y-axis functionality, or dual-spindle setups.

In terms of space, machining centers usually require a larger physical footprint due to their gantry structures, automatic tool changers, and chip conveyors. Horizontal machining centers tend to occupy even more floor area compared to vertical ones. Turning centers are often more compact, especially single-spindle configurations designed for high-volume turning tasks, making them a better choice for shops with limited space.

Energy consumption also differs. Machining centers with high-speed spindles and multiple servo axes tend to consume more power, especially during continuous multi-axis operations. Turning centers, being mechanically simpler and often focused on linear movement, are usually more energy-efficient per unit of material removed.

Programming complexity can also influence operational cost. Machining centers often require more advanced CAM programming, especially for multi-axis toolpaths and collision avoidance in tight setups. While turning centers are generally easier to program for standard turning operations, integrating live tooling, C-axis control, and synchronization with sub-spindles can significantly raise the skill requirement for both programming and operation.

From a maintenance perspective, machining centers demand more attention due to the number of moving parts, tool changers, and potential for thermal deviation. Tool magazine calibration, spindle alignment, and axis accuracy need to be monitored regularly. Turning centers, although simpler in structure, still require careful maintenance of turret indexing systems, spindle bearings, and coolant delivery—especially in long-run, unattended cycles.

In short, machining centers incur higher costs and complexity but offer greater flexibility and broader application coverage. Turning centers offer a more compact, cost-effective solution when high-volume, rotational part production is the primary focus, with maintenance and operational simplicity being key advantages.

Conclusion: Machining Center vs Turning Center

In the world of precision manufacturing, understanding the distinctions between machining centers and turning centers is more than just technical knowledge—it’s about choosing the right tool for the right job. These machines reflect two philosophies of motion and material interaction: one centered on a rotating tool carving through complex surfaces, the other on a spinning workpiece shaped with consistent precision. Whether you prioritize multi-surface versatility or high-efficiency turning, each machine type brings unique strengths to the production floor, and mastering those differences is key to optimizing output, quality, and cost.

This comparison also underscores the importance of choosing equipment partners who not only understand these nuances but also build machines that embody them. At Rosnok, this philosophy drives everything—from our vertical machining centers to advanced turning solutions. With a portfolio tailored for real-world industrial needs and decades of expertise in CNC technology, Rosnok quietly powers manufacturing lines across the globe, where precision, reliability, and adaptability are not optional—they’re expected.